Economist Ashoka Mody & Greta Thunberg

Last Saturday, in the middle of the night, I was listening to Business Matters on the BBC World Service. At 18.30 minutes into the programme, there is a piece on the Greta Thunberg’s speech to the UN. She said:

We are in the beginning of a mass extinction and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you.

Then Business Matters played a section from ‘Marketplace’ on Minnesota Public Radio, An economist responds to Greta Thunberg. “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal asked Ashoka Mody, Professor of International Economic Policy at Princeton, what he thought of Thunberg’s speech.

Professor Mody thought Greta’s speech was a very important statement, “cutting out a political path on which economists must now travel”.

However…

Growth makes lives better

Ryssdal asked why economic growth matters. Mody said growth matters because we want peoples’ lives to be better but growth had better be the kind of growth that helps peoples’ lives and makes climate change less daunting than it is.

Mody agreed with Ryssdal that while developing countries grow very quickly now to raise their standards of living, it’s different for the United States. Professor Mody said that the United States will not grow at the same rate as India but even slow growth in the United States is important for the US: Even in the US there are poor people.

US growth stimulates world trade

He also said that even relatively slow growth in the United States feeds into world trade, which makes other countries prosper as they participate in global trade. There’s no question that all of these need growth.

A Green New Deal will help poverty & help people pay debts

Mody thought the philosophy of the Green New Deal was the right one. We need to change the way we do things: more environmental creating a new avenue for innovation and investment, which will help people come out of poverty, helps people repay their debts.

Greta is right. Is Professor Mody wrong?

If Greta Thunberg’s characterisation “fairy tales of eternal economic growth” refers to global or national accounts, she may be right. It is true that production is improving so that fewer emissions are made from individual production methods but this improvement is not enough to overcome the effects of increased production.

The rate of improvement for the whole world has been about 2% a year for a few decades. That means if world GDP had stayed constant (i.e. zero economic growth) emissions would have fallen by 2% a year.

However, world GDP has risen faster than 2% a year, more than offsetting the improvement. This has led to rising greenhouse gas emissions. (For a fuller explanation see Climate destruction: Economic growth)

If this trend in the historic rate improvement in production emissions continued without any economic growth, emissions would reach zero in 2067. Currently, world greenhouse gas emissions are 6.5 tonnes CO2e per person, if they fall at the 2% rate they would total over 160 tonnes CO2e per person, before reaching zero. This easily exceeds the remaining carbon budget of 64 tonnes CO2e per person.

To keep within budget, emissions must fall at a rate greater than 5% a year. Without reduced production this looks very unlikely. Based on recent history, Greta Thunberg is right: In the next few decades economic growth is a fairy tale.

Can Professor Mody also be right? Can the ‘philosophy of the Green New Deal’ rescue the situation so that economic growth is possible and greenhouse gas emissions fall fast enough to fit within a budget of 64 tonne CO2e – or any other reasonably safe budget.

What gives Professor Mody his optimism? The answer may be that in specific circumstances, localised economic growth is possible, which also causes greenhouse gas emissions to fall.

For example, the increased production of large wind turbines by Siemens in Hull will cause emissions to fall substantially. Perhaps production in Central Hull is following “the philosophy of the Green New Deal”, with increased production and reduced emissionsIt will be difficult to reproduce this nationally or globally.

If it can’t, a reduction in economic output will be necessary in the medium term avoid climate disaster. That’s degrowth.

However, Professor Mody says

Professor Mody has a compelling TEDx talk, Can Economic Growth reduce Social anxiety and political polarization. He shows for several countries’ voter participation is high when economic growth is high and low when economic growth is low. When economic growth is low economic mobility is low but inequality is high. Parents worry that their children may have a bleaker life than theirs and their children will not have opportunities to climb the economic ladder. It is when opportunity fails that a fear sets in and that fear grows into a political alienation, which leads to more support for extremist politics.

Professor Mody notes that in conditions of low growth and high inequality parents who are on the upper rungs of the economic ladder are able to provide their children with better education which gives them an economic advantage over poorer parents.

In areas where production has moved on, children can be left with economic hardship.

For example, in Ivrea, once the fabled home of Olivetti, once referred to as Italy’s Silicon Valley, a number of children now live with their pension owning parents and compete for low-paying service sector jobs in such facilities as call centres.

Professor Mody stresses the need for more education for three reasons, saying:

• Education has been essential for economic growth since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

• Education offers for most individuals the only real prospect of upward mobility.

• Education typically makes more informed political participation.Only education simultaneously can raise economic growth, increase upward mobility and create a more informed and politically active public.

Widespread and high-quality education is essential must receive the highest priority to break this destructive loop from low growth, pessimistic expectations to political anger.

Yet what do we see we see that the share of educational expenditures in national budgets have either remained flat or have in fact declined.

Degrowth and inequality

To save the climate degrowth is necessary. Can the political disaster Professor Mody might predict be avoided? For example, can inequality be reduced without growth?

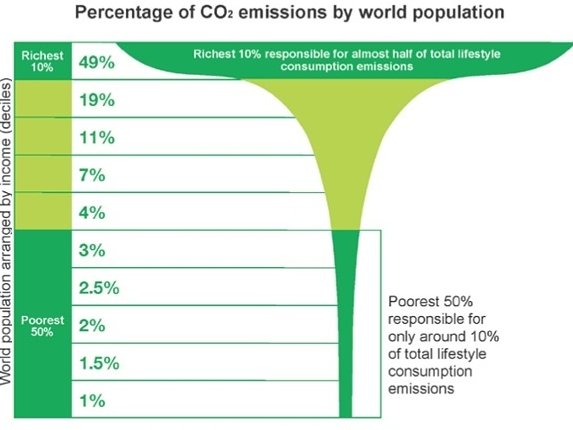

Roughly half of greenhouse gas emissions are created by the richest 10% of the world’s population. The poorest half of the population cause 10% of the emissions. A simple solution would be to tax emissions (mostly caused by the affluent) and use the revenue to support the poor. This would curtail flying, driving cars, eating beef and other activities causing large greenhouse gas emissions. It would also decrease inequality.

Is degrowth necessarily unpleasant?

Stopping frequent flights and pricing beef and lamb out of diets won’t make life too uncomfortable.

A bigger problem is the car. However, car free cities can be much cheaper and more pleasant to live in as the ‘lost’ report from the European Commission argued.