National Planning Policy & Green Belts

The Government have asked for views on their approach to updating to the National Planning Policy Framework.

This is Part 3 of my submission.

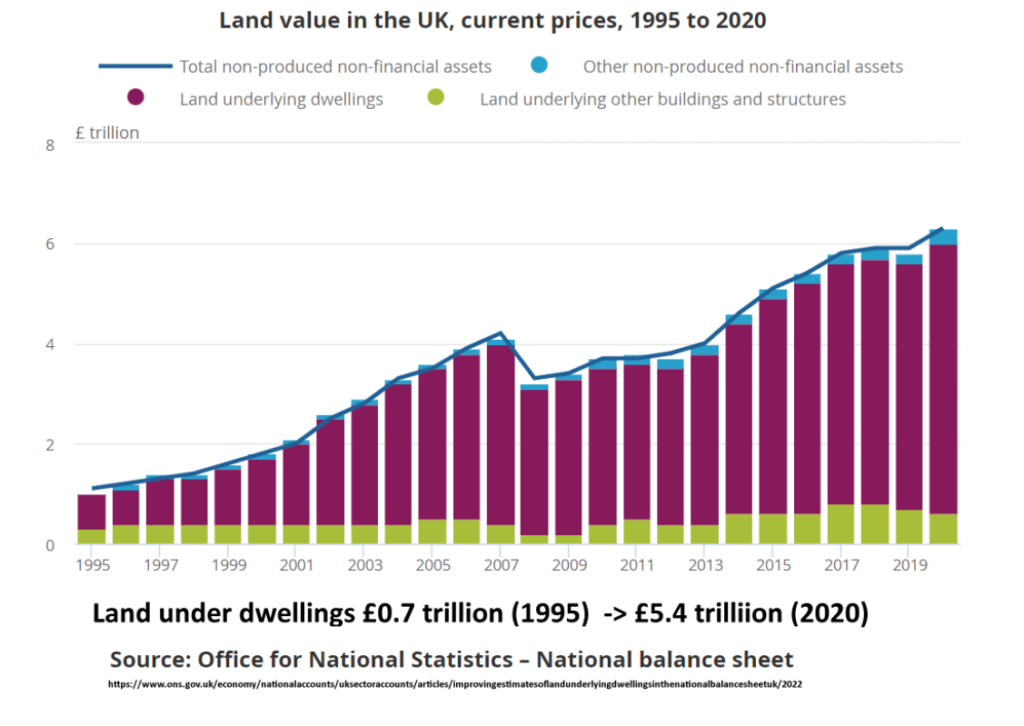

The “value of land” has soared of the past few decades

Nearly all the “value of land” in the UK is not farms or country estates: It is the “value of land under dwellings”. Nearly all “value of land under dwellings” is not the value of land as land for growing food or playing golf. It’s the value of Property Location Rights – the rights to have buildings on land.

Demand for housing has outstripped supply for the past few decades, causing large increases in house prices. This has transferred immense wealth from renters to property owners transferring wealth from the young and poor to the old and affluent.

A small part of the increased cost of housing may have been increased costs of building but nearly all of the increase can be seen as an increase in the value of the Property Location Rights. Granting planning permission creates property location rights. If the supply of planning permissions were increased (and hoarding by developers curtailed), the value of Property Location Rights would fall. This would be reflected in a fall in the cost of housing. A big fall.

A barrier to house building: Green belt policy

There are political barriers to new house building. These have been institutionalised in Government’s Green Belt Policy, which “aims to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open”. But what re the effects of this policy? In Time to dispel the Green Belt Myths and get Britain building Ilana Cantor writes

If the Government ever wants to solve the housing crisis, they need to step up and dispel the Green Belt myth that has become so entrenched within the British psyche. The romanticised notion of a “green and pleasant land” is strangling our cities and preventing the much-needed supply of houses.

Timothy Worstall of the Adam Smith Institute commented:

…the whole point of the green belt(s). [It’s] to stop any housing or other economic growth anywhere near where upper middle class people who make their living in our most important cities might want to live. That’s the whole point of it all.

Origins of Green Belt Poicy

Green belt policy originates in the Garden City Movement, started by Ebenezer Howard. In Garden Cities of To-morrow, Howard provided an outline of a garden city that promised a clean environment, free from air and water pollution, and an abundance of parks and open spaces. It advocated the advantages of urban living, which is near to open countryside. A report by Natural England and the Campaign to Protect Rural England, Green Belts: a greener future says:

The concept of Green Belt was initially suggested in the late 19th century. In 1898, Ebenezer Howard’s proposed Garden Cities were intended to be “planned, self-contained, communities surrounded by greenbelts, containing carefully balanced areas of residences, industry, and agriculture

It also says

The Green Belt covers nearly 13% of England, significant not only because of its extent, but because it provides both a breath of fresh air for the 30 million people living in or near to our largest towns and cities

Modern Green Belts are too large

However, Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities were quite small, with 30,000 inhabitants, containing much green space. They were divided into neighbourhoods of 5000 inhabitants, which were within a few minutes walk of their “green belts”. Current green belts enclose million of residents in much larger urban areas. The size means that most of these urban inhabitants are not close to modern green belts. For the “30 million people living in or near our nearest towns” the inhabitants must get in their cars and drive out of town: That is, if they have a car.

It is disingenuous to claim that these modern green belts bring a breath of fresh air to urban inhabitants. They are too distant – even with smaller green belts such the one that threatens to surround York. Here they are not everyday experiences – except for commuters looking out of their car, bus or train windows.

There is also a special clause in the NPPF that applies to places like York It’s “to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns”. I live in York and have ridden my bike around most of the outskirts. I cannot think of a single place in the (proposed) green belt where York’s “special character” is visible, except the top of York Minster, which is visible from many miles away – way outside an green belt.

Government justification of Green Belt Policy

The NPPF states “purposes” of Green Belt Policy, which are:

- a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas;

- b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another;

- c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment;

- d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and

- e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban

To someone who comes from the Medway Towns in Kent (Strood, Rochester, Chatham and Gillingham) purposes (a)&(b), “sprawl and merging”, are no cause for worry. Within the “unrestricted sprawl” of the towns there are large areas of green space: The Great Lines, The Darland Banks and Jackson’s Fields. Urban areas with large enough green spaces that allow greenness to be experienced with the conurbation.

Public opinions

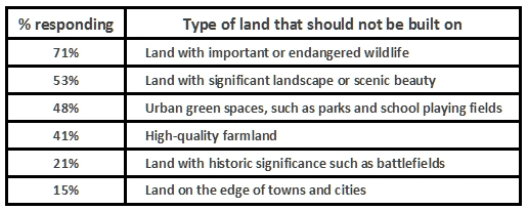

Green space within urban areas is much more valued than distant green belts as research for the Barker Review of Land Use Planning. This contained a poll by Ipsos MORI that asked the question “What types of land is it most important to protect from development?’. It allowed respondents three choices each from six possibilities. The results:

Greenbelt is ‘Land on the edge of towns and cities’. It comes bottom of this list and gets less than a third of the votes given to ‘urban parks and playing fields’. City parks are very much more valued than green belt land.

Brownfield sites

Purpose (e), “to assist in urban regeneration” is the NPPF’s way of promoting development on brownfield sites but many of these sites are ideal for becoming nature parks close to local inhabitants, such as St Nicholas Fields in York or The Brickfields in Lower Halstow, North Kent. These bring “greenness” much closer to people than the greenbelts that surround them.

Food production, rewilding and homes

In the Ipsos survey, “high quality farmland” gets a reasonable score, perhaps based on the idea of national food sufficiency. As climate changes, this may become a significant issue. However, as the BBC’s Vegetarian school dinners noted

- a third of carbon emissions come from food

- most of this from animal products

- 85% of UK farmland is for animal products

Using animals as a food source takes much food to feed them and turns this food into not much food at all. In his book, Regenesis, George Monbiot argues that current farming methods are destructive and need to be largely replaced by rewilding to save the environment. In Silence of the lambs, he says:

There are just two actions needed to prevent catastrophic climate breakdown: leave fossil fuels in the ground and stop farming animals. But, thanks to the power of the two industries, both aims are officially unmentionable. Neither of them has featured in any of the declarations from the 26 climate summits concluded so far.

Reducing animal farming is essential to tackle climate change. This will release a very large proportion of UK land for rewilding to sequester greenhouse gases – and building homes.

Appendix: From the Adam Smith Institute

In his report The Green Noose, Tom Papworth writes:

- Despite academics, politicians, and international organisations recognising that the UK is facing a housing crisis, it is currently far less developed than many imagine, especially when compared to similar countries. Indeed, only two members of the EU 27 have less built environment per capita than the UK: the Netherlands and Cyprus. 90% of land in England remains undeveloped, and just 0.5% would be required to fulfil this decade’s housing needs.

- Green Belts are not the bucolic idylls some imagine them to be; indeed, more than a third of protected Green Belt land is devoted to intensive farming, which generates net environmental costs.

- & etc.

Download the report The Green Noose.