Carbon footprints & wildfires

The first of two blogs commenting on recent reports from the Committee on Climate Change.

This first questions the official version of climate science that the Committee follows.

The official science of climate change

Since the industrial revolution pollutants from human activities have caused the surface of the Earth to warm. This is global warming (aka. climate change). The main pollutants are called greenhouse gases because they are gases, which warm the Earth in much the same way as the glass panes in a greenhouse warms the plants inside. The gases allow more of the sun’s heat in and let less of it out. The main greenhouse gases are:

- Carbon dioxide (CO2);

- Methane (CH4);

- Nitrous oxide (N2O);

This warming is changing global weather patterns and causing sea levels to rise: Other effects include life-threatening heat waves, stronger hurricanes, increased droughts and increased flooding. In many places in the world with poor infrastructure, climate change makes life even harsher causing starvation and mass migration.

Well-founded predictions suggest life will become harder for future generations in all parts of the world – driven by climate shocks caused by increased concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. For reasons like these, international treaties are being made aimed at limiting global emissions of greenhouse gases.

International treaties are based on scientific assessments available at the time the treaties were made. Climate treaties can last several decades. However, climate science is changing at a quicker pace, so the ‘official’ science embedded in existing treaties becomes outdated.

Bureaucracy of climate treaties

International treaties on climate change are made through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 197 countries (most of the countries in the World) participate in the UNFCCC, which holds conferences (Conferences of the Parties or COPs), where climate treaties are negotiated and agreed.

The UNFCCC usually relies on the scientific assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Their assessments are informed by publications in scientific journals and the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP). CMIP coordinates work on climate computer models.

In short:

- Basic science comes from scientific publications and the CMIP models

- The IPCC compiles assessments, which inform the UNFCCC

- The UNFCCC enables international treaties on climate change

There have been two important treaties agreed at UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol in December 1997 and the Paris Agreement in December 2015.

The Kyoto Protocol committed its Parties to ‘internationally binding’ emission reduction targets and placing “a heavier burden on developed nations”.

The Paris Agreement relied on the concept of “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) where individual countries would commit to reducing national greenhouse gas emissions by amounts they would self-determine. Although self-determination is a weakness, a redeeming feature of the agreement was the requirement that signatories report regularly on their greenhouse gas emissions.

Sadly, after these treaties, it is still true that the poorest and most vulnerable people are being affected the most but the world’s richest people emit the most of the greenhouse gases.

The ‘official’ science in climate treaties

The main assessments from the IPCC, occur approximately every six years as ‘assessment reports’. The first Assessment Report was completed in 1990. The Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) was completed in 2013. The cycle of these reports means that the negotiations for new treaties through the UNFCCC can happen at best every six years. Additionally, the necessary IPCC bureaucracy means that the assessment is somewhat out-of-date by the time treaties are made.

These reports inject a snapshot of climate science into international treaties. As well as the issue of time lags, these snapshots have been shown to be subject to political and commercial influences. These influences mostly downplay the dangers of climate change.

For example, in How Big Oil Tried to Capture the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Mat Hope describes the attempts by the lobby group, the Global Climate Coalition to influence the IPCC’s work.

The lobby group focused its efforts on trying to constrain the strength of the IPCC’s statements about human causes of climate change in the run up to the UN’s annual climate meeting in Kyoto in 1997, where world leaders agreed to the world’s first global climate change treaty. Officials from President George W. Bush’s administration would later credit the GCC for influencing his decision to abandon the landmark Kyoto treaty.

Mat Hope also reports minutes of meetings showing “intensive lobbying by [GCC] representatives and ‘assistance from several countries’”. The IPCC is, of course, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – governments are in charge and may influence assessments.

In RealClimate, Close Encounters of the Absurd Kind, Ben Santer describes how , in the 1995 meeting of the IPCC, pressure from the delegations from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, the IPCC weakened the statement on the attribution of climate change to human activity from “appreciable” to “discernible” – with some help from the UK delegation.

Additionally, in October 2018, the IPCC released an important report (SR15) saying that unprecedented global action was required to stop global warming exceeding 1.5°C to avoid the worst effects of climate change. At the UNFCCC COP24 meeting in December 2018, the report was blocked by the governments of the United Stated, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

Even before IPCC assessments are made, there are influences basic climate science: Modern science is for qualified professionals who have the budgets to carry out their work. If it is given funding basic science has status and can influence policy. Without funding and status, it cannot.

Funding bodies have the leverage to influence basic science. There is an obvious example in the United States, where President Trump’s attempts to cut climate science budgets show a dislike of climate science.

Funding can also have an effect on the careers of academics – advancing those with work in tune with funding authorities as Casey and Ashley discuss in Paying the piper: the costs and consequences of academic advancement.

Changing responsibility for climate in the UK

Prior to 2008, climate science was the responsibility of the Department of Food, Environment and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). At that time, DEFRA’s Chief Scientific Adviser was Sir Robert Watson, who argued strongly that human actions are causing global warming. In November 2000, as Chair of the International Panel on Climate Change he said:

The overwhelming majority of scientific experts, whilst recognising that scientific uncertainties exist, nonetheless believe that human-induced climate change is inevitable. Indeed, during the last few years, many parts of the world have suffered major heat waves, floods, droughts, fires and extreme weather events leading to significant economic losses and loss of life.

Sir Robert was unpopular with certain commercial interests. In April 2002 the United States pressed for and won his replacement as IPCC chair. However, in 2007 he became Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the department that had responsibility for climate change.

When the UK’s climate change act was passed in 2008, the responsibility for the climate change moved from DEFRA to the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). The fear that this move meant climate change policy was subservient to fossil fuel interests was reported in the Guardian:

Fossil fuel companies enjoy far greater access to UK government ministers than renewable energy companies or climate campaigns, an analysis by the Guardian has revealed…

Carolyn Lucas MP was quoted

Perhaps if its ministers spent a little more time with the country’s leading scientists and renewables experts, rather than nestled in the pockets of fossil-fuel companies, they’d be a little more enlightened.

In 2016, the Department of Energy and Climate Change was taken into the Department of Business, Energy and Information Services (BEIS). BEIS is not a climate-friendly department. It promotes economic growth, claiming it can be ‘clean’ growth’:

Clean growth means growing our national income while cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Achieving clean growth, while ensuring an affordable energy supply for businesses and consumers, is at the heart of the UK’s Industrial Strategy. It will increase our productivity, create good jobs, boost earning power for people right across the country, and help protect the climate and environment upon which we and future generations depend.

It is easy to see that, without miraculous and immediate changes in world economies, economic growth for the whole world will bring climate disaster. Most of the responsibility lies with rich countries like the UK that have per capita greenhouse gas emissions much greater than the global average.

Another example of attitude to climate at BEIS is their support for fracking. Shale gas causes greenhouse gas emissions directly leakages. It can be worse than coal for its impact on climate.

Support for policies, which increase greenhouse gas emissions, means that BEIS has reasons for downplaying global warming. However, BEIS is now the sponsoring department of the Meteorological Office and the associated climate research centres such as the Hadley Centre. It is now the main purse holder for UK government sponsored climate science.

In short, since 2008, the responsibility for climate science has moved from Defra, when Sir Robert Watson was Chief Scientist, to the DECC, which listened to fossil fuel interests, to the overtly business orientated BEIS.

BEIS is the sponsoring department for the Committee on Climate Change. The Secretary of State for BEIS chooses the CCC’s members.

Climate claims from BEIS

BEIS has recently claimed the UK is “leading the world yet again in becoming the first major economy in the world” to pass laws to end its contribution to global warming by 2050 and bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero. BEIS also says :

The UK has already reduced emissions by 42% while growing the economy by 72% and has put clean growth at the heart of our modern Industrial Strategy.

However, BEIS’s emissions are “territorial emissions”, which do not include emissions from international air travel, international shipping and the emissions embodied in imports: Shut a steel works in the UK and territorial emissions decrease because the emissions from steel making drop from the statistics but the emissions from making the replacement steel imported from overseas are not counted in the UK. Those emissions are counted in the country of origin.

A better way of measuring carbon emissions, which avoids this “steel works” issue, is to measure the carbon emissions caused by consumption that happens in the UK. These include emissions from international aviation, shipping and the emissions from making the goods we import. These emissions are also called the UK’s carbon footprint.

The Office of National Statistics (ONS) explains the different ways of measuring national carbon emissions, in particular, pointing out that the UK’s carbon footprint has fallen by about 10% since measurement started in 1997. A steady fall at this rate would take nearly 200 years to reach net zero.

The latest measurement available for the UK carbon footprint (in 2016), gave the UK consumption emissions as 784 million tonnes of CO2e. That is 11.9 tonnes CO2e per capita. This is at least 50% higher than the world average. The remaining carbon budget for keeping global temperatures within 1.5°C is 64 tonnes CO2e. The average UK citizen exhausts this in six years.

But BEIS still tweets: “The UK is taking world-leading action – cutting emissions by 44% since 1990.” The tweet contains the hashtag #ClimateChangeTheFacts.

Missing feedbacks: permafrost, wetlands & forest fires

A recent UPI article Arctic wildfires continue to burn, releasing record amounts of CO2 is very worrying. The increase in wildfires is a climate feedback that has not yet been incorporated in climate models. In 2016, scientists at DECC identified melting permafrost emissions, forest fires and wetlands decomposition as feedbacks missing from the models.

Although the IPCC special report, Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15), makes an “expert judgement” about the effects of permafrost and wetlands feedbacks, no estimates have been made for the effects of the wildfire feedback. Increased wildfires show the ‘official’ IPCC assessment of climate change in SR15 to be an underestimate, but these are not the only missing feedbacks: As the scientists at DECC said:

The feedbacks you mention are certainly important, although there are several other feedbacks that could be included but are currently too difficult to model. As knowledge and understanding advances, they will be added to the climate models.

Remaining carbon budget: 47 tonnes CO2e

Because feedbacks are missing from the official science of the IPCC, the science of treaties, lags behind the science of the real world.

SR15 does give an estimate of the reduction of remaining carbon budgets by climate feedbacks from melting permafrost and emissions from wetlands.

This would reduce the per capita remaining carbon budget to 47 tonnes CO2e.

Further, the emissions from increased forest fires were not included in the climate models that informed SR15. Other feedback emissions may also be absent.

Carbon dioxide and methane

The two main greenhouse gases causing global warming are long-lived carbon dioxide and short-lived methane (CH4). Here they are taken as representatives of short-term and long-term atmospheric pollutants.

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is less than 0.5% of the concentration of carbon dioxide but it causes about a quarter of the warming. However, chemical processes mean that any methane emitted now decays in just over a decade, so its warming effect is limited in time – but continued emissions mean methane’s concentration is still increasing. There are differences of opinion among scientists on the importance of reducing methane emissions.

Xu and Ramanathan argue for policies that reduce methane emissions quickly and create a short-term reduction in global warming – but they also say this must be accompanied by reductions in carbon dioxide emissions in the short & medium-term. Additionally, in the long-term carbon dioxide must be extracted from the atmosphere.

Other scientists, like Ray Pierrehumbert and Myles Allen, argue that because the warming due to methane emissions is short-term it is much less important than CO2 because CO2 remains in the atmosphere and heats the Earth for a much longer time. The heating from methane will have warmed the Earth’s surface for the decade or so before it decays but the warmer surface will radiate heat back to space. Unless the Earth is near the peak temperature this temporary warming is not so serious.

Ray Pierrehumbert has written:

Suppose we are outrageously successful, and knock down anthropogenic methane emissions to zero, which would knock back atmospheric methane to a pre-industrial concentration of around 0.8 ppm… This gives us a one-time cooling of 0.4°C.

And…

… since methane responds within a decade to emissions reductions, we still get the full climate benefit of reducing methane even if the actions are deferred to 2040.

In The exit strategy (2009), Myles Allen et al. emphasise a longer term and say:

Short-term measures that reduce 2020 emissions of potent but short-lived gases but commit to greater emissions of CO2 overall could actually be counterproductive.

Allen’s comment doesn’t exactly contradict Xu and Ramanathan. They do not advocate reducing methane emissions to go easy on carbon dioxide emissions. However, the approach of Pierrehumbert and Allen suggests a reduced worry about the short-term and methane emissions.

Xu and Ramanathan address the short, medium and long-term and have three separate strategies:

- Short-term reduction by reducing methane and other short-lived climate pollutants.

- Short, medium and long-term reductions in CO2 emissions.

- Medium to long-term policies to extract CO2 from the atmosphere.

Xu and Ramanathan’s cite the carbon cycle feedback as one of the reasons for reducing short-term climate forcing. The current wildfires in the Arctic may be an example of how keeping the Earth’s surface a bit cooler in the short-term could reduce the risk of liberating large quantities of greenhouse gases, including the long-lived carbon dioxide, which must eventually be extracted from the atmosphere.

And as the scientists from DECC said “there are several other feedbacks that could be included but are currently too difficult to model”. These may make short-term warming more dangerous.

Global Warming Potential

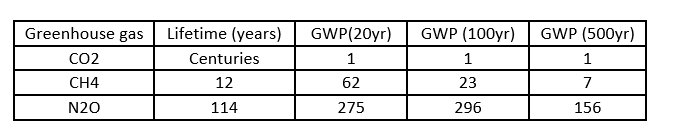

At the third Conference of the Parties (COP3), the UNFCCC agreed on a method for measuring the strength of warming due to different greenhouse gases. This method is called Global Warming Potential (GWP). For COP3, GWP was used to compare the warming over specific time periods: 20 years, 100 years and 500 years. The warming of CO2 is defined as 1 for this method. The warming of other gases is given in relation to CO2. Here is a table comparing carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), showing the values agreed in COP3:

The warming due to methane is 62 times that of CO2 if measured over 20 years. One tonne of methane can be described as 62 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent or CO2e(20). However, when measured over 100 years one tonne of CH4 has the warming effect of 23 tonnes of CO2. This can be described as 23 tonnes CO2e(100).

These numbers suggest that for the consideration of long-term climate change (e.g. 100 years) methane emissions should be taken less seriously than for the consideration of the short-term (e.g. 20 years). Choosing to measure GWP over 100 years suggests that the advice of Xu and Ramanathan to make immediate reductions in methane emissions is taken seriously less seriously.

At COP24 in December 2018 “the international community decided to standardise reporting under the Paris Agreement transparency framework using the GWP100 metric.”

This choice of GWP is embedded in national policies – as seen in the report on fracking from the Committee on Climate Change, A role for shale gas in a low-carbon economy? by Dr David Joffe, Head of Modelling at CCC. He chooses to use GWP(100) because it “is the internationally recognised basis for emissions accounting and is used by the CCC as standard across all its analysis.”

This “internationally recognised basis” implicitly downplays the importance of dealing with short-term warming effects like those caused by methane emissions.

Fracking and agriculture

On shale gas, David Joffre says:

For [shale gas] to have higher lifecycle emissions than coal per unit of energy contained in the fuel, the methane leakage rate during shale gas production would need to exceed 11% – this is implausibly high even where regulation is lax.

However, if Dr Joffre had chosen to use the GWP(20) measure for methane instead of choosing to use the GWP(100) measure the necessary leakage rate would be about 4% for break-even with coal.

Serious concerns about the fugitive emissions from fracking are reported by Robert W Howarth in Methane emissions and climatic warming risk from hydraulic fracturing and shale gas development: implications for policy.

significant quantities of methane are emitted into the atmosphere from shale gas development: an estimated 12% of total production considered over the full life cycle from well to delivery to consumers, based on recent satellite data.

And …

When methane emissions are included, the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas is significantly larger than that of conventional natural gas, coal, and oil.

Robert Howarth uses the short-term measure of methane’s warming potential, GWP(20). In choosing GWP(100) for methane, David Joffe of the CCC takes near-term methane emissions less seriously than Robert Howarth of Cornell.

Downplaying the importance of methane emissions must be welcome to those supporting fracking, such as BEIS. Agricultural interests may also welcome the comment by Myles Allen in the Oxford Martin’s News:

We don’t actually need to give up eating meat to stabilise global temperatures,” says Professor Myles Allen who led the study (meat production is a major source of methane). “We just need to stop increasing our collective meat consumption.

Xu and Ramanathan, with methane reduction as the first part of their strategy, must surely disagree.

The Committee on Climate Change: emissions counting

The Committee on Climate Change was setup to monitor progress under the Climate Change Act of 2008 towards a reduction in UK greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050. The Act defined “UK greenhouse gas emissions” as territorial emissions, which are much lower than the UK’s carbon footprint, the emissions due to UK consumption.

The Committee has used the UK Government’s acceptance of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement as a reason for extending “UK greenhouse gas emissions” to include international aviation and shipping.

In Net Zero – The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming (May 2019), the Committee used the UK Government’s acceptance of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement as a reason for extending “UK greenhouse gas emissions” to include international aviation and shipping. However, even these ‘enhanced territorial’ emissions currently miss 33% of UK consumption emissions.

The Committee concedes BEIS’s rationale for not using consumption emissions, at least partially:

consumption emissions will only reach net-zero once the rest of the world’s territorial emissions are also reduced to net-zero. At this point the UK can expect to pay slightly more to cover the costs of low-carbon production of the goods we import.

The Committee has recently submitted their 2019 Progress Report to Parliament, Reducing UK emissions. This acknowledges the government line on economic growth, which originates BEIS. For example:

The Clean Growth Strategy, the UK’s plan for emissions reduction, provides a solid foundation for the action needed to meet a net-zero GHG target

The Clean Growth Strategy promotes economic growth, so is clearly at odds with saving the world from dangerous climate change.

In Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, the CCC recommend that the 2050 target for UK GHG emissions should be a 100% reduction in GHGs from the UK on a production basis. However, the Committee’s advice is that consumption emissions should be reported at the same time. The Committee’s 2019 report to Parliament, notes consumption emissions are much higher than territorial emissions:

The UK’s consumption emissions were estimated at 784 MtCO₂e in 2016, around 56% higher than territorial emissions (including international aviation and shipping) of 503 MtCO₂e (Figure 1.6).

The report points out that in the long-run the gap between consumption and territorial emissions could diminish:

Actions taken by our trading partners under the Paris Agreement will further reduce the carbon intensity of goods imported to the UK and hence UK consumption emissions. This would also close the gap between consumption and territorial emissions.

The 56% gap between the Committee’s enhanced territorial emissions and consumption emissions is large one.

The Committee should advise the Government to use consumption accounting in emissions targets.

The Committee on Climate Change: official science

The Climate Change Act has a target date of 2050 and this is naturally reflected in the 2019 Progress Report. The thirty years to 2050 are roughly three times the lifetime of methane.

The Committee uses the GWP(100) measure for methane because it is “the internationally recognised basis for emissions accounting”. This measure assigns a lesser importance to methane emissions than the GWP(20) measure and the Committee clearly backs the views of Allen and Pierrehumbert in the Committee’s 2019 report to Parliament, it says:

Emissions of short-lived GHGs do not need to be rapidly brought to net-zero, but rather stabilised and then slowly decreased to prevent continually increasing global average temperature.

This is implicitly downplaying the role of carbon-cycle feedbacks, some of which are clearly missing from climate models. Two feedbacks, permafrost thawing and methane release from wetlands, were mentioned in SR15. The Committee’s 2019 report says:

Earth system feedbacks such as permafrost thawing and methane release from wetlands, are expected to slowly release carbon into the atmosphere over decades to centuries. This may be around 100 GtCO 2 (2 – 3 times annual global emissions) over the century.

SR15 describes this 100GtCO2:

Expert judgement is both used to estimate an overall uncertainty estimate and the estimate to remove 100 GtCO2 to account for possible missing permafrost and wetlands feedbacks.

“Expert judgement” is a term that is too opaque.

The Committee should make the case for choosing the judgements of Allen and Pierrehumbert over those of Xu and Ramanathan. It is not sufficient that the ‘official science’ of the UNFCC has made this choice, implicitly downplaying the role of carbon-cycle feedbacks.

The Committee should not accept science because it is ‘official’ but because it is the best science available.

Postscript: Remaining carbon budget.

A remaining carbon budget is the quantity of greenhouse gases that can be emitted before a global climate disaster occurs. A common interpretation of ‘climate disaster’ is reaching a 1.5°C rise in the global average temperature since pre-industrial times. In Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, there is a section on remaining carbon budget:

Estimates of the remaining carbon budget (the total amount of future net CO2 emissions consistent with keeping warming below a certain level) for limiting warming to below 1.5°C has recently been updated by the IPCC. Keeping warming to below 1.5°C with at least 66% probability corresponds to less than 10 – 14 years at current global emissions rates.

Elsewhere, I have calculated the remaining carbon budget as 64 tonnes CO2e per person [Note 1]. The latest figure available for the UK’s carbon footprint is 11.94 tonnes CO2e per UK citizen per year. Citizens of the UK exhaust their fair share of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C in less than six years. Twice the rate of the global average.

The Committee should acknowledge that UK emissions are currently much higher than the global average, exhausting the UK’s ‘fair share’ of the remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C in about six years.

[Note 1]

In the recent Working paper from the Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP), Zero Carbon Sooner — The case for an early zero carbon target for the UK , Professor Tim Jackson calculates a remaining UK carbon budget to be 2.5 GtCO2 (2,500 million tonnes of CO2). Divided amongst the 66 million population, this averages 39 tonnes CO2 per person. In terms of the composite measure for greenhouse gases, Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (CO2e), this averages 49 tonnes CO2e per person.