Garden Cities and Green Evolutionary Settlements

Garden Cities and ‘Green Evolutionary Settlements’

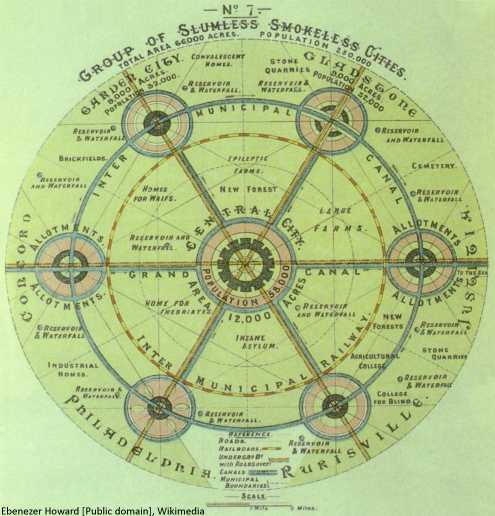

Ebeneezer Howard’s plan for Garden Cities

Finding ways of living, that do not challenge life on Earth, is urgent and difficult.

It must be atop priority for planners of villages, towns and cities.

Here I compare the well established idea of Garden Cities with a different, ‘Green Settlement’, approach.

Garden Cities

Garden Cities were proposed by Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928). He wanted them to be planned towns that combined the benefits of the city and the countryside and avoid the disadvantages of both. They were big enough to have a city’s qualities but small enough to have nearby countryside. Howard saw them as separate satellite towns to an existing Central City.

In 1899 Howard founded the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA). The TCPA has described a Garden City as:

a town designed for healthy living and industry of a size that makes possible a full measure of social life but not larger, surrounded by a rural belt; the whole of the land being in public ownership, or held in trust for the community.

Howard had two Garden Cities built: Letchworth Garden City (founded 1899) and Welwyn Garden City (founded 1920). Both are 30 minutes train ride from London, Kings Cross. The TCPA says the principles of Garden Cities include ‘capturing land value for the community’, ‘housing types that are genuinely affordable’, ‘a wide range of local jobs’ & etc. (More in Appendix 3) In re-imagining garden cities for the 21st century the TCPA also says:

Early publicity for Welwyn made much of its Hertfordshire location and the quality of its housing, but also trumpeted benefits such as being able to walk to work in clean airy factories and offices without tedious and time-consuming journeys … and the aim was to make a town small enough for everyone to be within walking distance of the centre in one direction and open countryside in the other. At a projected population of some 30,000, with a net density of [30 houses to the hectare], it would be big enough to support a diverse economic base and various facilities.

Welwyn Garden City today

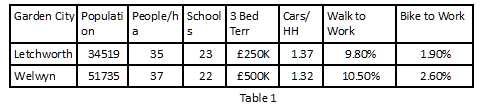

Travel statistics show that, in these two Garden Cities, about 10% of working residents now walk to work; 60% go by car and just over 10% by rail. 10% work at home. The rest are split between bus bike and other forms of transport. 30% work in Greater London and 40% work outside their home district, leaving 30% to work more-or-less locally.

An estimate of the number of schools has been added from a count on Google Maps.

Population and density (2016) from CityPopulation.de. House prices (approximate)

from Zoopla. Travel statistics from Hertfordshire Traffic and Transport Data Report

(2016)

The original idea of local employment and nearby countryside saw walking as the

main form of transport. This is not the case now. Few households of Letchworth

and Welwyn – 20% or less – are carless. The statistics show that car travel is by far

the most dominant mode.

Planning a Garden City

Planning for a completely new town or city is a large and complex undertaking: The Letchworth and Welwyn Garden Cities took decades to plan and build. Garden cities were planned as new places to live, built on greenfield sites, planned for a better, pleasanter way of life – with walking as the main means of transport..

The story line for Garden Cities was: Old cities have failed. Let’s start again.

Now the original vision has faded: Letchworth and Welwyn are not the walking cities that Howard imagined and there are no ‘housing types that are genuinely affordable’.

Have Garden Cities failed. Should we start again on this grand scale?

Green Evolutionary Settlements

Nice map of a green settlement – with housing and food production.

An evolutionary approach

A Green Evolutionary Settlement (GES) is a new type of development aimed at promoting cheap and friendly lifestyles that ‘do not screw the world up’. They follow some Garden Cities principles but also incorporate financial and legal enforcement mechanisms to promote good living. These mechanisms are integral to this type of design.

In order to avoid carbon footprints that are planet destroying, these settlements will be mostly free of cars: Here, ‘car’ means the sort of car that is today sold from a car show room. More appropriate personal transport may be tried but, like Ebeneezer Howard’s initial Garden City principles, travel distances will be shorter.

Howard’s Garden Cities, separated from an older larger Central City, had populations of 30,000+. A Green Evolutionary Settlement will be an addition to an existing larger settlement, sharing its activities. As urban add-ons, these green settlements are unlikely to reach populations of 10,000. They may start with much smaller populations – initially perhaps a few hundred dwellings. They are built mostly on greenfield sites adjacent or very near existing cities.

The aim of these settlements is to infiltrate existing cities with ways of living that are pleasant and are environmentally, economically and socially sustainable – with the emphasis on environmentally sustainable. Unlike Garden Cities, they are not separate start-again disjoint developments. They make a start then the evolve.

This evolutionary aspect is also reflected in a recent report on removing greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere, Greenhouse gas removal, by the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering recommended a similar evolutionary approach: “We will learn as we do,” said Prof Henderson, the chair of report team. This reflects the urgency of climate change and the need for radical, yet to be fully tested technologies.

Symbiotic with existing settlements

From the outset these Green Settlements should be designed not just to provide for the needs of its own residents but also to to the populations of neighbouring settlements. They provide services which can spread ‘greenness’ to its neighbours. Simple examples: a high quality electric bus service or a local market garden. In return, the new settlements may use some of the existing services of their neighbours.

Green Evolutionary Settlements need much less pre-planning than Garden Cities because of their size and a more direct symbiotic relation with existing settlements. To find sustainable lifestyles (that also make life worth living), trials are necessary – many trials. Because they are smaller, many Green Settlements can be prototyped easily, and they can be evaluated in much shorter times.

But the Garden City experiment …

In contrast, the ‘Garden City experiment’ has produced just a few examples over many decades – and these examples do not function as planned: Compared to the original aim of Garden Cities, based on walking to nearby work and leisure, the current residents use cars and travel much larger daily distances. This alone means that they have carbon footprints in the planet destroying class.

Note: The direct emissions from motoring are not the only reason.

Car ownership is an expression of wealth and wealth is a determinant

of carbon emissions: In Distribution Of Carbon Emissions in the UK,

Preston et al. say:

The inclusion of transport emissions suggests that the

richest 10% of households are actually emitting more

than three times the carbon emissions of the poorest 10%.

This is one of the reasons that the two Garden Cities have large carbon

footprints that, if repeated world wide, would would threaten life on

Earth in a few decades. However, this is true for most UK residents.

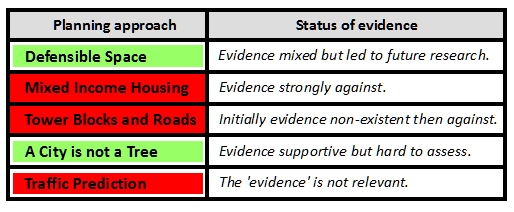

Green settlement design is best being evolutionary and organic: Start with a small core of houses round central facilities and a transport hub, while working out the details of how to proceed next. Past experience (in the 20th Century at least) shows that planning on the grand scale usually fails. My article Five Planning Policies explores some of these failures. Only two of the five planning approaches had any merit:

Table 2

One that had merit was the idea that interconnected networks of urban areas works much better than when urban areas have delineated functions as described in Christopher Alexander’s A city is not a tree. Green evolutionary settlements do not make these mistakes Alexander outlines: They are add-ons intended to integrate with existing neighbouring urban areas.

The urgency of our environmental problems means the need to try radically different ideas requires a new – and quicker – approach: One that incorporates measures to get results.

Financial and legal mechanisms

In A new Ministry of Works, I suggest that a new government department should be created that can oversee a programme of new settlements, with extra powers that cut through the ‘red tape’ of planning law (but for these new settlements only). For example, a new settlement may define standards for vehicles that are allowed on local roads. Some might even allow Segways or modern versions of the Sinclair C5.

The most important way that the Green Evolutionary Settlement idea is different is its approach to local economies: The life in the settlement is shaped – consciously shaped as part of the design process – by financial and legal mechanisms. These mechanisms are to be as important a part of the design as site layouts and housing types. This was suggested in Pedestrian apartheid – RSPCA News (1976):

The aim of the association is to promote research and discussion into economic and legal mechanisms (such as rents, service payments and covenants) which may be used to improve the quality of our environment.

Existing examples of such mechanism are the covenants against keeping pigs which are found in the deeds of small terraced houses or the service payments made by the residents of service flats.

Such mechanisms could be of great value in allowing a wider variation in the type of local environment that can remain economically and socially viable. This would not only give a greater range of choice but would also allow the experimentation necessary to find those forms of local environment best suited to the future.

These mechanisms can improve the way residents affect the lives of their neighbours and be better world citizens. Examples of the use of financial and legal mechanisms already exist and are part of urban design. The RSPCA approach would make this integral to settlement design.

One example can be found in Hackney, where some new housing developments are designated as car-free and legal agreements restrict the rights of residents to have cars by refusing car parking. Hackney Transport Strategy 2014-2024 says:

10.4 Car Free developments

Car Free developments can be defined as development with no car parking facilities for residents or visitors other than those as needed to meet the needs of disabled people. Occupiers of the development are restricted from obtaining on‐street parking permits by legal agreement.

Car free developments support a number of objectives of the Transport Strategy given that they have a role to play in improving the attractiveness of the local area for walking and cycling, help create more ‘people oriented’ environments and can reduce local air pollution and noise levels.

The areas chosen for this strict form of enforcement are ones with good public transport. This particular form of enforcement is local in scope but also affect world wide pollution levels by discouraging use of private cars. It supplements the carrot’s of good public transport and better cycleways with the stick of legal enforcement. For the residents, who don’t want to rely on the car that’s very good news: Living car-free is much cheaper and pleasanter.

Does that seem a bit authoritarian? These new settlements are not prisons. They are new environmentally sound and affordable additions to the housing market. The rules may be less noticeable than those at your local golf club.

One of the most important aims of Green Evolutionary Settlements is to create lifestyles that have low carbon footprints. To this end quite novel mechanisms can be used. I am a member of the Pollution Tax Association, founded 1992. The members of the association – there are too few of us – agree to pay a notional ”carbon tax”, which usually ends up as donations to good causes. The aims:

– To bring an awareness of the pollution caused by everyday economic activity within a market economy and to promote the control of pollution by the use of pollution taxes.

– To encourage individuals to voluntarily pay substitute pollution taxes to organisations which can compensate the polluted and fight for the control of pollution.

In the UK, if we were serious about climate, we would be trialing new settlements in which taxes were levied on the residents for their pollution. The income could be used to support local services. There are many forms this support could take – one reason to include good economists in the design process. An example: After a holiday flight to The Maldives, the resident local carbon tax to support local shops or food production, supporting local jobs.

This prompts an interesting question: Could a Green Settlement benefit from a payments under any carbon offset scheme?

Because of a pioneering way of charging for facilities, the ‘all included’ holiday is an interesting example of financial and legal mechanisms to create a local environment – one that works for many customers. Appendix 5 looks at Butlins Holiday Camps. They may not suit everyone but the message is “If you don’t like holiday camps, don’t go.” Many holiday makers liked them and, as the appendix reports, many do now.

A similar message may be applied to Green Evolutionary Settlements but several trials are needed to find those that work for the residents and for the environment.

A rich gene pool of settlement types is required

Making planning work differently said:

We need to experiment with planning ideas to create rich gene pool of settlement types with stricter rules for living, so that the settlements that work can become part of our pattern book. An example would be planners granting permission for a settlement where all households must have electric cars or one in which or one in which a defined percentage of residents work locally.

We need an approach that will spawn different settlement types and measure their outcomes in terms of defined parameters.

The use of financial and legal mechanisms can expand the types of settlement that are in our pattern book. Settlement types that would suit me – and many others – are ones where few motorists can be residents – either by legal covenants or by pricing mechanisms such as mentioned in RSPCA News.

New Green Settlements will create more choice. More importantly they will help to find ways of living that don’t cause climate catastrophe.

Appendix 1: Parameters that describe settlements

Making planning work differently also said:

In order to classify different settlement types we need parameters that describe them. Some parameters may turn out to be more important than others. Some may turn out to be unimportant. Here’s my first list of settlement parameters:

Size of settlement

% of residents employed locally

% of food produced locally

% of goods bought from local retailers

Social class of the residents

Average weekly travel distances.

A measure of ecosystem services

Average carbon footprint of residents

Protection of ecosystems

Most of these parameters are not now used in planning – a planning restriction that demanded that a certain percentage of food should be produced locally would almost certainly be rejected on appeal – but the challenges of this century mean we must experiment in terms of these parameters.

Appendix 2: Becoming car free

Probably the biggest problem for “advanced economies” in “developed nations” is becoming car-free. We can stop most of our airline flights, eat much less meat, cut our electricity and power consumption – even as it becomes ‘greener’ – but reducing local travel is harder. To be effective this requires changing not just the carbon footprints of our personal transport but also reorganising the spatial patterns of the places where we live.

The Modern Automobile Must Die discusses the impact of cars as they are currently defined. A new specification for personal transport, the ‘car’. In the short term this could be effected by restrictions on what could be allowed on Green Settlement roads. Islington and Hackney Councils are banning certain types of vehicle for certain hours of the day: Petrol and diesel cars are banned from east London roads to tackle toxic air:

Drivers will receive a £130 penalty if they use anything other than electric or hybrid models in areas of Hackney and Islington between 7am-10am and 4pm-7pm on weekdays.

Green Settlements could be much more radical for their local roads. e.g. no private vehicles that weigh more than 100kg or have top speeds higher than 15 mph.

Changing car technology alone is just not sufficient. And as Bjorn Lomborg points out, electric cars are not the answer:

Even if Lomborg’s objections can be overcome in the longer term – they can’t happen soon enough to save the climate.

The aim of Green Settlements is that they become centres which spread their ‘greenness’ to nearby urban locations. This will require much more than changing personal vehicles. They are not the distant add-ons that the Garden Cities are to Ebeneezer Howard’s Central City. They infiltrate the Central City beginning it’s transformation to something better that enables pleasant ways of life that don’t cause a climate catastrophe – and for the next few decades that means phasing out mass car use.

Appendix 3: Garden City Principles

Garden City Principles listed by the Town and Country Planning Association are:

— Land value capture for the benefit of the community.

— Strong vision, leadership and community engagement.

— Community ownership of land and long-term stewardship of assets.

— Mixed-tenure homes and housing types that are genuinely affordable.

— A wide range of local jobs in the Garden City within easy commuting distance of homes.

— Beautifully and imaginatively designed homes with gardens, combining the best of town and country to create healthy communities, and including opportunities to grow food.

— Development that enhances the natural environment, providing a comprehensive green infrastructure network and net biodiversity gains, and that uses zero-carbon and energy-positive technology to ensure climate resilience.

— Strong cultural, recreational and shopping facilities in walkable, vibrant, sociable neighbourhoods.

— Integrated and accessible transport systems, with walking, cycling and public transport designed to be the most attractive forms of local transport.

Appendix 4: The Garden Suburb

The Garden City Ideal was a precursor to the Garden Suburb as described by the Cultural Landscape Foundation:

A distinct variant known as radial garden suburbs is characterized by a geometrically ordered arrangement of streets and land subdivision, with tree-lined residential streets radiating outward in tiers from a centrally located circular park. The Garden Suburb is distinguished from the Garden City by is emphasis on residential uses, rather than balancing residential, commercial, and industrial uses as a Garden City would.

Wikipedia describes the difference between Garden Cities and Garden Suburbs:

The concept of Garden Cities is to produce relatively economically independent cities with short commute times and the preservation of the countryside. Garden Suburbs arguably do the opposite. Garden Suburbs are built on the outskirts of large cities with no sections of industry. They are therefore dependent on reliable transport allowing workers to commute into the city. Lewis Mumford, one of Howard’s disciples explained the difference as “The Garden City, as Howard defined it, is not a suburb but the antithesis of a suburb: not a rural retreat, but a more integrated foundation for an effective urban life.”

and

Smaller developments were also inspired by the garden city philosophy and were modified to allow for residential “garden suburbs” without the commercial and industrial components of the garden city.

Appendix 5: An example: Butlins holiday camps.

Butlins in the 1950s

Wikipedia describes the opening of Billy Butlin’s first camp at Ingoldmells, near Skegness:

When the camp opened, Butlin realised that his guests were not engaging with activities in the way he had planned; most kept to themselves, and others looked bored. He asked Norman Bradford (who was engaged as an engineer constructing the camp) to take on the duty of entertaining the guests, which he did with a series of ice breakers and jokes. By the end of the night the camp was buzzing and the Butlin’s atmosphere was born.

Full-time living in a holiday camp, may not be ideal for everyday life but these camps are examples of geographically limited settlments, albeit short stay, with their own internal financial organisation and rules. Butlin’s camps often get good reviews, like this one from Trips with a tot:

We just got back from our first 4 night stay at Butlins on one of their Just For Tots break, and wow: it was way better than I expected. Our holiday was so good that we booked for next year before we had even left… yes, really! I know it sounds crazy, but it was sooooo fun.

The cost is ‘all included’:

Imagine this: entertainment with shows, play areas outside and inside, pop up library, places to eat and drink, amazing swimming, meet and greets, arcades, fairground, characters, Little Tikes, bowling… and entertainment, activities, swimming, etc., is all included in your stay which is the cherry on the top.

‘All included’ enables facilities that would not be possible were they to be charged separately. There are a few reasons for this: Payment in advance for unlimited use means parents don’t have to worry whether a ride on the ‘Rides for Tots’ is value for money or have the bother of using their chosen payment method every time.

Making facilities free at the point of use also maximises the value to the holiday makers as a whole, allowing those families that are relatively indifferent (i.e. those that would pay a bit but not quite enough) – to let their children go on a ride. It also encourages greater use of the facility, maximising the use of a fixed asset.

Those that don’t like the product, the ‘all included’ holiday, can stay away.

Postscript 12 oct 2018

Victor Gruen: Shopping Malls into settlements

I have discussed Victor Gruen in earlier posts but have just found this piece on Smithsonian.com about one of my heroes from the seventies, Victor Gruen:

The father of the American shopping mall, the Austrian-born architect Victor Gruen, envisioned the mall as a sort of European-style town center for the American suburbs. He saw malls as climate-controlled Main Streets, with post offices, supermarkets and cafes, set amidst larger complexes with schools, parks, medical centers and residences. You’d hardly need to drive at all. Gruen found cars repulsive.

But only part of Gruen’s vision caught on: the climate-controlled gray box, famous for encouraging car culture rather than stopping it. In 1978, the elderly Gruen railed against what his idea had become.

“I would like to take this opportunity to disclaim paternity once and for all,” he said. “I refuse to pay alimony to those bastard developments. They destroyed our cities.”