Mixed communities – a failed policy

#MixedCommunities

Mixed communities – a failed policy

The “mixed communities” paradigm for housing development aimed to mix poorer people with more affluent neighbours to avoid the problems of large sink estates. It has been central to housing policy for more than a decade. A Parliamentary Select Committee in 2003 reported:

90. Several witnesses drew attention to the mistakes of the 1950s and 1960s when large council estates were built which tended to include high concentrations of poorer households. In its new programme, the Government must avoid creating ghettos by ensuring that different tenures are integrated into new developments. New approaches are required by private developers and housing associations to create mixed tenure schemes.

The decline of council housing

During the 1980s many council estates declined. The rot really set in with Thatcher’s housing policy as Andy Beckett outlined in a Guardian article, The right to buy: the housing crisis that Thatcher built:

“Now revived by David Cameron, the right to buy social housing was a key Conservative policy in the 80s: populist, profitable, and with its disastrous effects yet to come .”

In 2003 Guardian Columnist Amielia Hill described the decline:

‘There’s a new social class now that’s growing up from underneath all the others,’ said Karen Law, from Sheffield’s Manor estate. ‘It’s the underclass. They’re today’s teenagers and they have no future.’ …

‘Twenty years ago, the Manor was considered the crème de la crème of housing estates,’ said Law. ‘Now you can walk round and take your pick of the empty houses, if you can crowbar off the boards from the windows. The council has let this area die.’

The mixed communities policy

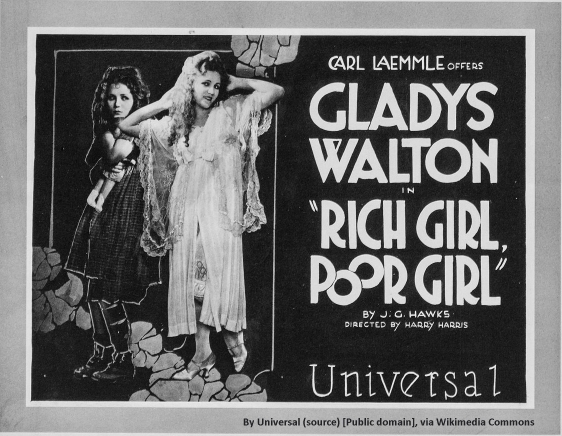

I didn’t really want to use this picture to illustrate the contrast between rich poor neighbours because it looks distractingly sleazy but couldn’t find anything appropriate, which I could use without paying copyright fees and/or understanding the copyright status of the image. I would rather have used that brilliant Toffs and Toughs photo.

Against a background of the decline of council housing, the “mixed communities” policies emerged. For example, in the 2009 Fabian pamphlet In the Mix, James Gregory thought we must avoid ‘apartheid cities’ through a policy of mixed communities:

We need to pursue housing mix with real conviction. This means integrating public housing with private housing, not just in special project ‘mixed communities’, but across the full range of our housing stock. Though this kind of mix is currently considered best practice in planning guidelines, it is too often only honoured in the breech.

For some, the policy still has force. In 2016 the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Estate Regeneration: Briefing for expert panel was still promoting “mixed communities” :

Mixed tenure has become a key housing policy objective for governments over the last 25 years. In 1993 the Joseph Rowntree Foundation published a groundbreaking report by David Page warning that housing associations risked repeating the mistakes of the past by building large estates with high child densities and concentrations of vulnerable tenants. Since then the idea that mixed communities deliver better social outcomes than mono-tenure estates has become central to policy on new development and the regeneration of social housing.

The less wealthy residents

Less wealthy residents didn’t necessarily relish mixing with wealthy neighbours, as Catherine Mallinson pointed out in a comment on How the Joseph Rowntree Foundation could do more for the poor

I lived in an “affordable” house with my husband and two children. Both of us parents were on minimum wage. The housing was at The Croft, Heworth Green, not a JRHHT development but it was meant to be affordable according to the conditions of the planning permission. We simply couldn’t afford the rents and the council tax (band E).

Of about 100 houses or flats only about 10 were social housing or part owned. Many of the other neighbours were wealthy. The people in social housing were friendly and we got on together. We did not get to know the wealthy ones and they seemed to look down on us.

We swapped with someone in Tang Hall. Where I live now it is affordable, social and a typical community. It is a neighbourhood where people are on lower incomes or they are students.

Hadrian Avenue – TangHall

Hadrian Avenue – TangHall

Mixed communities treat a symptom of inequality not its cause

Doubts about mixed communities as an effective way to reduce deprivation were in another JRF report by Paul Cheshire in 2007. In Are mixed communities the answer to segregation and poverty? He wrote

This study challenges the belief that mixed communities are an effective way to reduce deprivation and social exclusion…

The author concludes that mixed neighbourhoods treat a symptom of inequality, not its cause, and the problem is poverty and not where people live. He argues that there is evidence that living with similar people – for both rich and poor – can generate some advantages.

Doubts on the mixed communities policy

In 2017 Jane Lewis wrote some Notes for Haringey Housing and Regeneration Scrutiny Panel. She took the following points from Mixed Communities: Gentrification by Stealth?:

Most mixed community policy is one-sided, seldom advocated in wealthier neighbourhoods and as for greater social interaction

(a) there is little evidence that people from diverse backgrounds ‘actually mix’

(b) that physical proximity leads to closer social ties is challenged

Other sources support the lack of social mixing (affirming(a)) but for those who have read Leon Festinger’s Social Pressures in Informal Groups: Study of Human Factors in Housing it is clear that physical proximity can lead to closer social ties (contradicting(b)). Festinger’s informal groups were young men with families, veterans of the Korean War. His detailed work unequivocally showed that friendships were influenced by proximity but his groups were reasonably uniform in nature, a uniformity reminiscent of Catherine Mallinson and neighbours in Tang Hall.

Mixing motorists and non-motorists.

Thankfully, the waning of the mixed communities policy makes it easier to discuss the separate development of motorists and non-motorists.

[The rest of this section has been moved to Car-free cities and pedestrian apartheid.]

Postscript: Lynsey Hanley’s Estates: An Intimate History

I should have mentioned this earlier- I have a copy somewhere. It was compelling reading. Here is an excerpt from a review by Blake Morrison in the Guardian

She too feels her heart sink whenever concrete towers or suburban boxes loom into view; she too sees them as “hutches” and “cages”. But having grown up on one estate (near Birmingham) and made her home in another (in east London), she resents the vilification of those who live there – all that sneering at scum, chavs, pikeys and the great unwashed. More importantly, she believes the greatest division between people today isn’t the work they do or what they earn or whether they have children, but the kind of homes they live in. And she wants to understand why being housed by the state has come to be seen as a confession of failure…

It wasn’t just Labour that supported postwar reconstruction. Under Harold Macmillan, 300,000 homes were built every year throughout the 1950s. But quantity was never matched by quality. And soon the fashion shifted towards the building of high-rise flats rather than houses, since it was quicker, easier and less wasteful of space to stack barracks vertically rather than on the ground. Modernist architecture played its part in this, too: Le Corbusier and his peers venerated concrete, and concrete came cheaper than brick. When asked (which was rarely) what kind of property they’d like to live in, most people said a house with a garden.

And this is where Corbusier lived:

Corbusier lived in a house designed by Eileen Gray.