Chasing productivity

(A second note on Oxford Economics)

Oxford Economics ignored climate change

In How robots change the world, Oxford Economics ignored climate change. Their report contains some interesting conclusions about how robots will destroy jobs by replacing workers while creating other jobs by generating economic growth.

However, as discussed earlier, any economic growth is not compatible with necessary climate constraints unless the relationship between GDP and greenhouse gas emissions can drastically change. Recent data shows this to be very unlikely.

Concentrating on the main greenhouse gas, CO2 [1], the relationship between emissions and the climate can be described as

CO2 Emissions = World GDP * Global CO2 Emissions Intensity

Also, as discussed earlier, Global CO2 Emissions Intensity has been falling much too slowly. This means CO2 emissions cannot fall fast enough unless there are substantial reductions in World GDP. The perception is that reductions in World GDP would cause unemployment. The point of this post is to show that this need not be the case.

Most of us believe employment gives dignity and worth. Martin Luther King said it like this:

So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs. But let me say to you tonight that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth.

AFSCME Memphis Sanitation Strike, April 3, 1968

For a decent society, unemployment is a bad option.

To lower GDP without causing unemployment, the average worker must produce less. Workers must become less productive, either by working shorter hours or by having jobs that are less intense, more fulfilling, more peaceful & etc. & etc.

Less productive jobs mean that the market value of labour falls and the rewards to owners of capital (e.g. the owners of robots) rise in proportion to wages. Currently, this would mean that the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. If we want to counteract this there are remedies are available.

Take from the rich and give to the poor

For some of us, taking from the rich and to give to the poor is a moral action. We can ignore the operationalist nonsense of Lionel Robbins and Percy Bridgman, who used a mistaken version of science to distance us from moral sentiments.

We needn’t be so apologetic as Thomas Piketty, who appeals to the affluent by arguing that concentrations of wealth “stirs discontent and radically undermines our democratic values”.

Redistribution is more fundamental than that: We have a biological basis for helping those in need. In The Compassionate Instinct, Dacher Keltner reports research by Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen who found that

when subjects contemplated harm being done to others, [the compassionate] regions in their brains lit up … [This] strongly suggests that compassion isn’t simply a fickle or irrational emotion, but rather an innate human response embedded into the folds of our brains.

Although there are many other considerations, redistributing from those that have too much to give to those that have too little is a good moral principle.

I believe that many of those that have too much wealth would agree and support a system of redistribution that would encompass everybody.

Polluters should pay

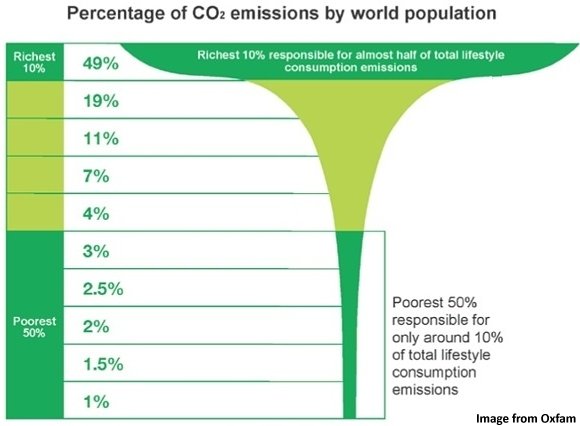

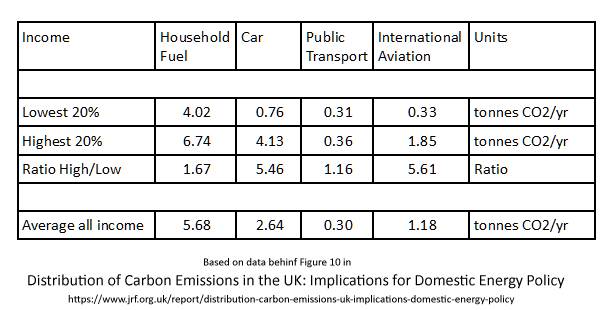

Another moral principle that can be used to justify redistribution is the polluter pays principle. The rich and affluent cause most of the carbon pollution in the world.

This is true also in the UK.

A redistribution of wealth and income based on polluting emissions is clearly a moral policy. The carbon fee and dividend promoted by the Citizens Climate Lobby and James Hansen is one way of putting this principle into practice. It should be world-wide.

Universal Basic Income

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a periodic cash payment delivered to all on an individual basis without means test or work requirement. In Why Legendary Economists Liked Universal Basic Income, Stephen Mihm points out that a wide range of economists who have supported a Universal Basic Income, including John Stuart Mill, Milton Friedman and JK Galbraith.

Currently, there is increased discussion of UBI, possibly influenced by the prospect of further deindustrialisation brought on by AI and robots.

Long discussions on UBI can be found elsewhere but it is relevant to point out that UBI could be used to counteract the falling value of labour caused by robotisation.

Labour subsidies

Other schemes are possible which address the fall in the value of labour. One that I first proposed in the 1970s gave tax breaks on VAT for employing workers balanced by an increase in the nominal rate. It was revenue neutral and had the effect of subsidising the bottom of the labour market, taxing capital and high paid labour. See…