The job apocalypse and climate change

See also Jobs, the AI revolution and climate change

The robot job apocalypse?

BBC Word Service has recently updated Robert Owen’s worries on the decline of labour as a factor of production. This time the concern is a new form of industrialisation: artificial intelligence. The programme, What Will Happen When Robots Take Our Jobs? has the introduction:

“Blue-collar jobs in industries like manufacturing have been disappearing for years but now white-collar work is under threat too. Machines are already taking roles that used to be done by journalists, lawyers and even anaesthetists. One recent study calculated that 47% of total employment in the US is at risk of automation in the next 20 years.

So what will happen to all the human beings who did those jobs? … And how will they earn money?”

The most powerful computer in the world

My first job was as a computer programmer in 1967 on the most powerful computer in the world, the Atlas Computer. It was a time when computer programmers were young and held in awe. Computer operators were mostly glamorous young women. The computer occupied the ground floors and basements of two large terraced houses in Gordon Square near University College. On hot days we went to the observation bay to take advantage of the air conditioning and watch the film set of magnetic tape drives starting, stopping, spinning rapidly and being changed by glamorous people. It was always sunny.

The expectations were sunny too. I remember being told that within a year we would have automatic language translation between English and Chinese. However, I have just met a smarmy friend who wanted to translate “Light of my life and many others” for a young woman he had met – but translated into Chinese. I tried Google translate and got 我的生活和许多其他的光. To check the result I reversed the translation. It came back “My life and many other light”. My friend wasn’t impressed.

However, there have been advances: Heinrich Heine’s “Ich weiss nicht was soll es bedeuten” Google translates to “I do not know what it signifies it”. Not exactly poetic but understandable and the York Council switch board can now get the right extension when a name is spoken – much of the time. Perhaps that optimistic work on mechanical speech recognition at the Atlas Computer Laboratory in the 1960s made a contribution to that – after decades of delay and an increase in the speed of computers by many millions of times.

The falling value of labour

But the hype of technological expectations aside, machines do reduce the value of labour. In 1978, I wrote Reducing the cost of labour to create full employment. This argued that microprocessor technology would cause a slump in the value of labour and that “the present phase of technological change is likely to bring a fall in the real value of labour, just as happened in the first industrial revolution.”

In the 1980s, it happened as I predicted. The Economist Magazine wrote

“The ‘labour share’ of national income has been falling across much of the world since the 1980s. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of mostly rich countries, reckons that labour captured just 62% of all income in the 2000s, down from over 66% in the early 1990s.”

Even if the robot job apocalypse, is more muted than the hype, it looks – at last – that artificial intelligence will have some effect on further reducing labour’s share of value. Leading to my conclusion that

“technological change can bring about conditions under which a large proportion of the population cannot live by the sale of their labour alone, and they should not be expected to do so.”

Growth and climate change

Growth of production and consumption can support the value of labour, sustaining employment and wages but we now have a constraint on production: climate change. Increased production means increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Of course, production can be de-carbonised – so that less greenhouse gasses are emitted for each unit of production – but as argued in Is Green Growth a Fantasy?, this cannot be done fast enough to avoid “dangerous climate change“. Production and consumption must be reduced.

Rather than cut our polluting activities by consuming less, the World Bank, the OECD and the governments of developed countries believe in “green growth”. The myth of economic growth with sufficiently reduced emissions to avoid dangerous climate change. We must reduce polluting activities like flying in planes, driving cars, eating beef and building brick houses – and office blocks of concrete and steel. This means a green recession rather than green growth.

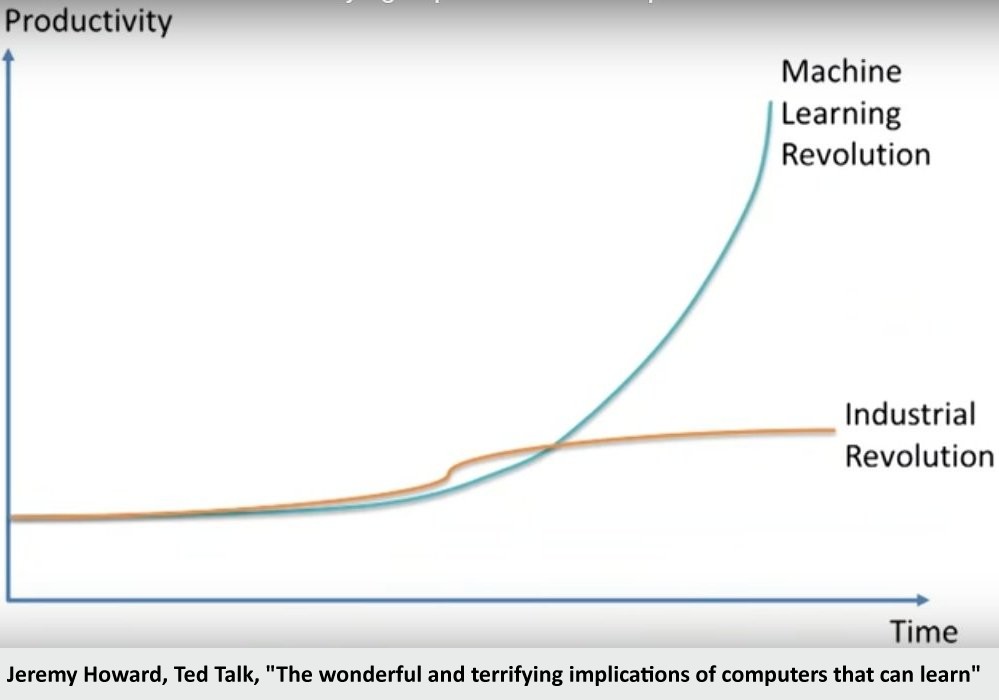

The latest form of industrialisation, artificial intelligence, will mean robots will do more jobs and devalue labour’s share of income – now stripped of the support from economic growth.

As labour becomes less valuable, wages must be supported by unearned income. We must all have our share of unearned income. from the world’s assets.

Hello

How do I subscribe to this blog?