Three failed eco-towns

Three developments that were aimed at sustainability

They are not even close

Carbon emissions and aspiring to be rich

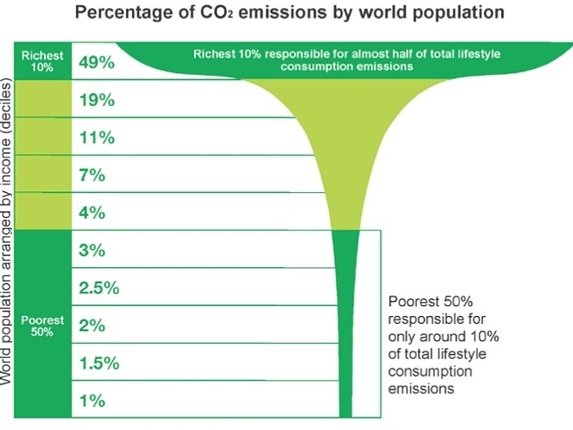

In their media briefing Extreme carbon inequality, Oxfam show the richest 10% of the world’s population produce half of Earth’s CO2 emissions and

The average emissions of someone in the poorest 10% of the global population is 60 times less than that of someone in the richest 10%

Naturally, the poor aspire to be rich but, as things stand, aspiring to be rich means aspiring to a high carbon lifestyle.

Required: high quality, low carbon lifestyles

If high carbon activities are avoided can a lifestyle be high quality and attractive enough to aspire to?

Some people in richer countries do commit to cutting their carbon emissions by avoiding carbon intensive air travel and everyday use of a car. They might also change their diet avoiding high carbon foods like beef. The more committed will chose to live somewhere where they can travel mostly by bike and occasionally by coach or train and will make sure the power and heat used in their homes is a low carbon as possible.

The very, very committed, like Simon Dale, have built their own low- carbon homes avoiding high carbon bricks and cement and using wood – and wood actually stores carbon that has been taken from the atmosphere.

It is interesting to see the reaction of Daily Mail readers to Simon’s house. The top rated comment (2271 up votes, only 14 down votes) said

“Well done you two! I would love to live in a house like this, you should be extremely proud of this wonderful home!”

There are a few individuals or families that can achieve low carbon life styles. It could be made easier to have a low carbon footprint if features like public transport, shops and employment are available in the neighbourhood. But first …

What is a “Low carbon” lifestyle?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (in IPCC AR5) have made an assessment of a “carbon budget” – a finite amount of carbon that can be burnt before it becomes unlikely we can avoid more than 1.5°C of global warming. Carbon Brief updated this budget to 243 tonnes of CO2. That’s an average of 33 tonnes for everybody in the world. Exceed this and 1.5°C of global warming is locked in.

Emissions from the average UK citizen exhausts this 33 tonne budget in two years. If the target is relaxed to accept 2°C of global warming, the average UK citizen runs out of budget (115 tonnes CO2) in six years. Fortunately, the average person in the rest of the world has much lower emissions.

Because of difficulties in climate modelling and the measurement of carbon emissions it’s hard to give a definite figure to the emissions of a low carbon lifestyle. Perhaps keeping below 2 tonnes CO2 per year per person as suggested in the Green Ration Book is a reasonable guide.

Developments which failed to be low carbon

In the UK, villages and towns have changed: while car ownership has increased, local buses have disappeared, local train stations have gone, local shops, pubs and post offices have disappeared, travel to work distances have increased and so have school runs. These changes have made low-carbon living harder.

Some argue that living in cities is the answer.

Urban density can actually create the possibility for a better quality of life and a lower carbon footprint through more efficient infrastructure and planning.

However, building extra houses, workplaces, roads, shops entails very large carbon emissions. To make a place for an extra resident emits enough carbon emissions to swamp the 33 tonne personal carbon budget for 1.5°C – and even the 115 tonne budget for 2°C.

Efforts to plan for neighbourhoods with low carbon footprints by better heating systems, building insulation and encouragement for non-car transport have been tried. There are three examples in the UK

- 1. The Beddington Zero Energy Development (BedZed) had high embodied carbon: At 67.5 tonnes CO2 for a flat, the embodied carbon was twice the 33 tonne remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C.

- 2. The “sustainable development”, Derwenthorpe in York has had the carbon footprints of the residents measured. Their average footprint is greater than the rest of York. The carbon emissions they save on the central biomass boiler they blow on increased travel. Embodied carbon was not measured.

- 3. North West Bicester is the first UK Government’s eco-towns to start construction. The aim to reduce embodied carbon by 30% probably puts it on a par with BedZED’s similar aim – an unimpressive target. With a new slipway onto a main road, it is likely to have residents for which commuting and shopping by car is usual.

The real shock is that the carbon footprint measured for Derwenthorpe was 14.52 tonnes per resident per year (using the REAP petite assessment method) . That is over seven times more than the 2 tonne low-carbon limit suggested by the Green Ration Book.

Pleasant but unsustainable

These may be pleasant developments that people in the rest of the world might aspire to – but they are clearly not the low carbon exemplars the world needs.

P.S. Some suggestions for a different approach are in A market in prototype neighbourhoods.

P.P.S. OK, these three developments aren’t actually proper towns so “eco-town” is a bit of poetic licence.

Postscript 17/03/2016

Advertised prices of homes in the eco-towns

£249,995 Seebohm, Derwenthorpe, York (Prices up to £474,995)

£475,000 North West Bicester 4 bed house

£225,000 BedZED 2 bedroom apartment

I wonder whether the info re. Derwenthorpe allows for the fact they have been burning gas as much as biomass due to underestimation of demand. We were told to expect both solar panel or photo-voltaic to be installed, some sort of mid-scale allotment areas, as well as electric powered, regular buses.

A small community garden, no solar power offering mentioned and full sized diesel buses on the hour is what we’ve got.

Having an ethos is great but policies and practices need to be followed through and well-managed to achieve the goal of being an eco-mini-town.